The first indexes were found in books as early as the 16th Century, and the word itself comes from the Latin for ‘one who points out’ or an ‘indication’ – literally using the forefinger to draw attention to something. Inherent in this is the understanding that what is being pointed out is factual, whether it is a specific word appearing on a certain page or something that will illuminate our understanding.

When it comes to indexing scholarly information, researchers have had the advantage of numerous providers supplying this information in a variety of ways over the last 60 years or so. From the early beginnings of Web of Science in the 1960s, through to Cabells’ directory in the late 1970s and Scopus in the 2000s, we have seen the size and complexity of the information indexed on academic publications develop in many different ways. However, the way data is included in indexes has been changing.

Digital era

When I first started working in academic publishing in the early 2000s at a publisher that predominantly published journals in business and management, I still remember the vivid blue directories of journal information that sat on the shelves above my desk. These were the hard copies of the Cabells Directory, published every two years, and a bible for us publishers keen to understand how our journals’ competitors were performing. These were the precursor to Cabells’ Journalytics and Predatory Reports databases, and while these are now fully searchable online, they are still curated by our team of journal experts.

However, since Elsevier’s Scopus entered the fray in the 2000s, two new indexers have entered the market in the shape of Dimensions and OpenAlex. They index content differently from traditional, manually curated offerings, and instead use digital technology to scan and assess relevant content. As such, while neither offers journal rankings like Scopus and Web of Science, both make at least a significant tranche of their data freely available to all users. So far, so good. However, an article published this month has brought the data they make available into question, as it claims that predatory journal information is shared without warning.

Cautionary tales

The article in question – ‘Prevalence of predatory journals in Open Alex’ – was written by Paul Donner, a researcher based at Deutsches Zentrum für Hochschul- und Wissenschaftsforschung (DZHW) in Germany, who used the access the institution had to Cabells’ Predatory Reports database to see if data on predatory journals were available through OpenAlex. The results were pretty shocking – using a sample of 400 journals listed in Predatory Reports (out of a total of over 19,000), Donner found that they were able to find details on 146 of these journals through OpenAlex, i.e., around 36% of the sample.

In addition, if we were to take the most well-known predatory publisher – OMICS – then its imprints are also well represented, with around 9,000 individual publications found for Allied Academies and 5,000 for Hilaris, for example. The author focuses his searches using OpenAlex, but if we look at just these two publishers on the Dimensions database (NB: For transparency, I used to work for Digital Science, which owns Dimensions), we can see, using its free access search, that there are journals from both Allied Academies and Hilaris:

- Allied Journal of Medical Research (Allied Academies) – 9 publications via Dimensions

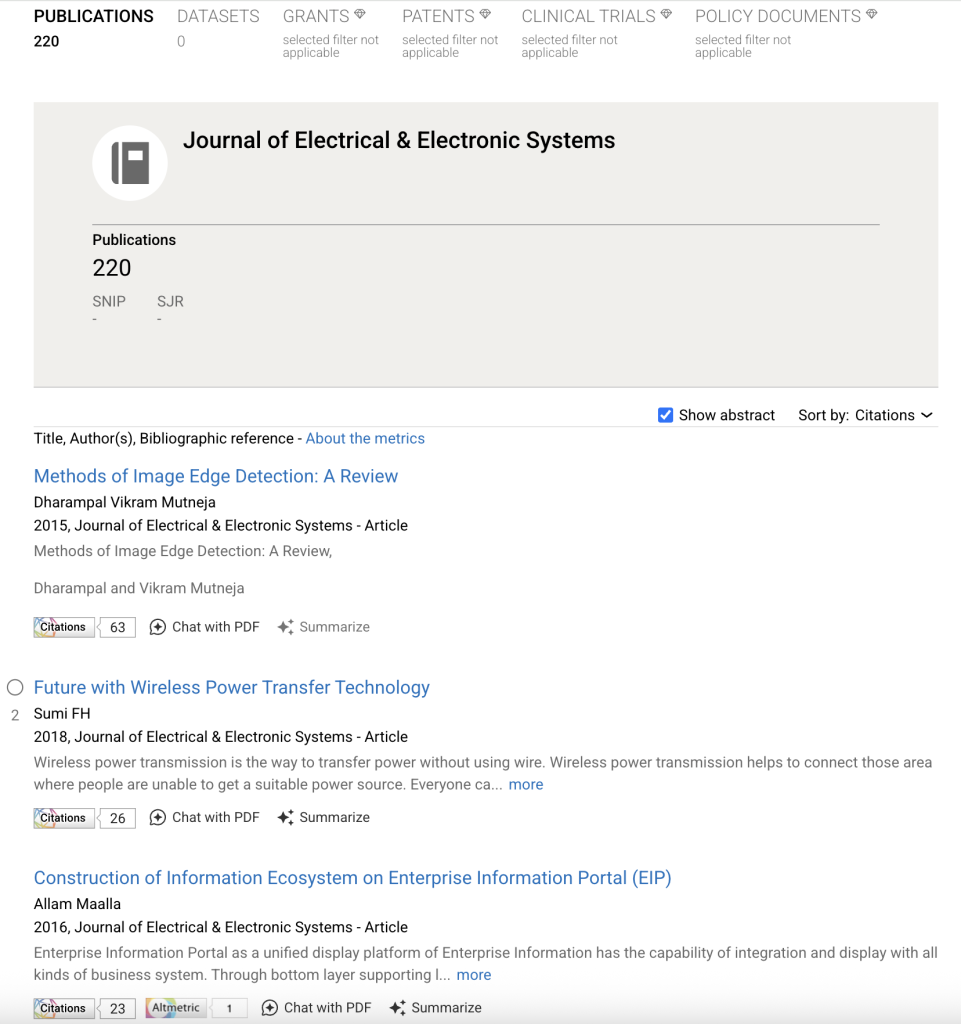

- Journal of Electrical & Electronic Systems (Hilaris) – 220 publications via Dimensions

Trust Factor

So, what does all this mean? Well, while some information on predatory journals does seem to be available via OpenAlex and Dimensions, there are many journals not covered on those services, and the data they provide should help steer would-be authors away from those titles that can be accessed (for example, none of the examples above have few citations recorded). However, nor are there any flags warning authors of the potential pitfalls in publishing their research in such journals.

The work of Donner and other researchers in highlighting these dangers – and indeed, Cabells’ team of journal checkers – at least shines some light on deceptive and illegitimate journals. However, this work is easily undone by the inclusion of information on them alongside legitimate journals in information providers such as OpenAlex and Dimensions. For decades now, authors have been told to ‘publish or perish’ to further their academic careers, but perhaps they should increasingly be reminded that ‘trust is a must’ when it comes to publications.

Simon Linacre is the Director of International Marketing & Development at Cabells, where he focuses on growing international markets and product development. He is passionate about helping authors get published and has delivered over a hundred talks, sharing useful publication tips for researchers.