With plenty of advice and guidance on the internet on how to identify and avoid predatory journals, many argue the game is up. However, while so many authors and journals slip through the net, numerous skills are required to avoid the pitfalls, not the least of which is, as one case study shows, being an amateur sleuth….

New Kid on the Block

The publishing industry is often derided for its lack of innovation. However, as Simon Linacre argues, there is often innovation going on right under our noses where the radical nature of changes are yet to be fully understood, for good or bad.

There was an attempt to hijack a journal…

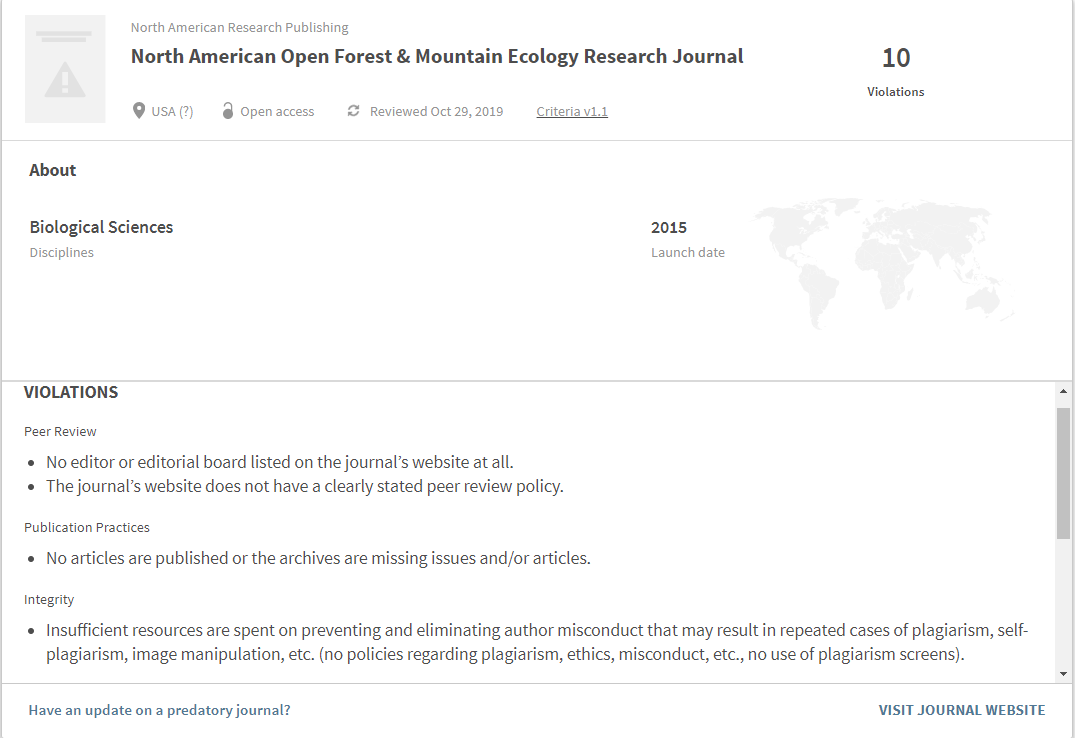

As our journal investigation team members work their way around the expanding universe of scholarly publications, one of the more brazen and egregious predatory publishing scams they encounter is the hijacked, or cloned, journal.

Cabells and AMBA launch list of most impactful Chinese language management journals

In his last blog post in what has been a tumultuous year, Simon Linacre looks forward to a more enlightened 2021 and a new era of open collaboration and information sharing in scholarly communications and higher education. In a year with so many monumental events, it is perhaps pointless to try and review what has … Continue reading Cabells and AMBA launch list of most impactful Chinese language management journals

Special report: Assessing journal quality and legitimacy

Earlier this year Cabells engaged CIBER Research (http://ciber-research.eu/) to support its product and marketing development work. Today, in collaboration with CIBER, Simon Linacre looks at the findings and implications for scholarly communications globally. In recent months the UK-based publishing research body CIBER has been working with Cabells to better understand the academic publishing environment both … Continue reading Special report: Assessing journal quality and legitimacy

They’re not doctors, but they play them on TV

Recently, while conducting investigations of suspected predatory journals, our team came across a lively candidate. At first, as is often the case, the journal in question seemed to look the part of a legitimate publication. However, after taking a closer look and reading through one of the journal's articles (“Structural and functional brain differences in … Continue reading They’re not doctors, but they play them on TV

Five dos and don’ts for avoiding predatory journals

HAVE YOUR SAY Publication ethics is at the core of everything that Cabells does, and it continually promotes all scholarly communication bodies which seek to uphold the highest standard of publishing practices. As such, we would like to express our support for Simon Linacre (Cabells' Director of International Marketing and Development) in his candidacy to … Continue reading Five dos and don’ts for avoiding predatory journals

Gray area

While Cabells spends much of its time assessing journals for inclusion in its Verified or Predatory lists, probably the greater number of titles reside outside the parameters of those two containers. In his latest blog, Simon Linacre opens up a discussion on what might be termed ‘gray journals’ and what their profiles could look like. … Continue reading Gray area

Bad medicine

Recent studies have shown that academics can have a hard time identifying some predatory journals, especially if they come from high-income countries or medical faculties. Simon Linacre argues that this is not surprising given they are often the primary target of predatory publishers, but a forthcoming product from Cabells could help them. A quick search … Continue reading Bad medicine

Look before you leap!

A recent paper published in Nature has provided a tool for researchers to use to check the publication integrity of a given article. Simon Linacre looks at this welcome support for researchers, and how it raises questions about the research/publication divide. Earlier this month, Nature published a well-received comment piece by an international group of authors entitled ‘Check for publication integrity … Continue reading Look before you leap!